Transformational

The transformation of iron and steel production from the traditional backyard artisanal puddling process to an industrial enterprise, constituted one of the pillars of the industrial revolution that catapulted civilization into the modern age and represents one of the monumental advances in human culture.Human labor and ingenuity acting upon the raw materials provided by nature results in something wholly new. That transformational relationship is the essence of culture. This, however, is a two-way street. When abandoned and left derelict, human creations are quickly overrun by and returned to nature. The transformative process must continue remorselessly or die.

Carrie Furnace, which operated for nearly a century, was at the center of the Twentieth century transformational process, particularly after its 1898 purchase by Andrew Carnegie and its subsequent integration with Homestead Works. The facility opened in 1881 as an independently-owned blast furnace (some sources say 1884) and was shuttered in 1978. The still standing Furnaces 6 and 7 operated from 1907 until the closing.

Photography of Carrie Furnace

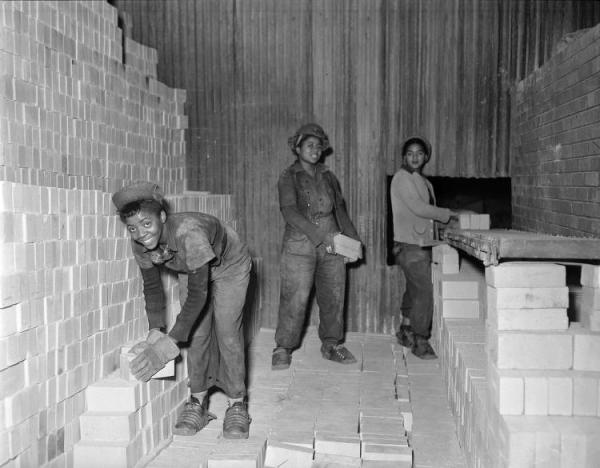

Overwhelmingly photographs of Carrie Furnace are of the works--the machines, structures, and structural remnants. Few are of the people. I particularly liked the one below, because it shows some of the people who worked there. In this case African-American women trainees learning masonry skills in October 1944.

Credit: Collection of William J. Gaughan, AIS 94:3, Archives Service Center, University of Pittsburgh

This picture was posted with the following caption: Pennsylvania's great demand for labor during World War II fueled a huge migration of southern African Americans to the Commonwealth. There they entered industrial jobs in record numbers, many receiving federally-funded training, and counseling from the NAACP on how to work along side white Americans.

What was produced at Carrie Furnace?

The product of the furnace was molten pig iron, produced by combining iron ore, limestone and coke in a furnace that forced superheated air through the vessel. Limestone drew off the impurities forming “slag” while the coke mixed with the iron as fuel, which both helped it to remain in a molten state for an extended period and would be a key ingredient for the next stage in the transformational process.

This raw material was shipped in torpedo cars across the Monongahela River over a Hot Metal Bridge, to the Homestead works to be refined into steel by forcing large amounts of air into open hearth furnaces where the molten iron was poured and combined with various alloying minerals and often some scrap steel. The fuel heating the open hearth furnaces was the carbon in the pig iron. Open hearth technology is no longer used in steelmaking, as arc furnaces and basic oxygen process are now used to produce steel more efficiently, in higher quality, and with a much higher proportion of scrap steel in the mix.

The resulting steel was harder, more flexible, and more malleable than cast iron. Rail for the railroads and structural steel were among the main finished products of the integrated mill.

What is was like to work at Carrie Furnace

The work was hot, heavy, dirty, and often dangerous work. Hot in the summer; cold in the winter.

In the video we watched one worker said something like, “It was dangerous; you had to be on your toes every minute.”

Based on my experiences in the mills, which admittedly were more recent, this was probably a bit of hyperbole. Because making iron is a timed process, the truth was probably closer to a description often used by steelworkers: “hours of boredom followed by moments of sheer terror” and periods of blindingly hard physical labor.

A sense of camaraderie developed on the job both because of the dangers faced and the need to watch each others’ backs, but also because of all the times spent waiting for the next stage of the process. These relationships continued off the job too in the bars, clubs, churches, and social organizations in the nearby communities, where most of the mill workers worked in those times. The Carnegie Library in Braddock, with its bathhouse, bowling alley, swimming pool, and concert hall provided a unique opportunity for many, especially the higher echelon employees.

Carrie Furnace in the News

Two recent articles in the Pittsburgh Post Gazette caught my attention.

The earlier article, "Carrie Furnace, UPMC-Braddock site redevelopments march” published June 30, 2012, by Len Barcousky, is a public notice of progress in plans by the Allegheny County Redevelopment Authority to convert some land around Carrie Furnace to office and industrial use. The authority decided to apply for $500,000 in state gaming funds to help pay for raising the eastern portion of the tract above the river's 100-year floodplain. Link: http://www.post-gazette.com/stories/local/neighborhoods-city/carrie-furnace-upmc-braddock-site-redevelopments-march-on-642633/#ixzz26HIgUEL0

The More recent was Annie Seibert’s August 16, 2012 article, “Locals take on Carrie Furnace restoration: Goal is to turn site into park, museum,” I’d earlier meant to repost. She quotes Ron Baraff, director of museum collections and archives for the Rivers of Steel Heritage Area joking, “It's not like there's a handbook: 'How to Preserve a Blast Furnace on $1.10 a Day.” Asked when does it become a museum, he replied, “It is.” The goal of the preservationists, according to Seibert, is to preserve the history of the steel industry for future generations. “There's nothing else like it," Baraff told her. Link: http://www.post-gazette.com/stories/local/neighborhoods-east/locals-take-on-carrie-furnace-restoration-649230/#ixzz26HHARhG4

What I hope to accomplish

Beginning in the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth centuries painters like Martin B. Leissner, Joseph Pennell, Aaron Harry Gorson, and Otto Kuhler began depicting what Barbara Jones calls "The Valley of Work." Early on photographers too turned their lenses to the plumes of smoke of the bustling industrial Pittsburgh landscape--men like Charles Torrance, Shelden Davis, Luke Swank, and Clyde Hare Countless others have continued to document its decline, demise and ruination.

My hope is to make a few compelling photographs that celebrate the transformational process and work represented by the surviving relics. I'm particularly interested in the opportunity to photograph the ruins in the evening and into darkness.

No comments:

Post a Comment